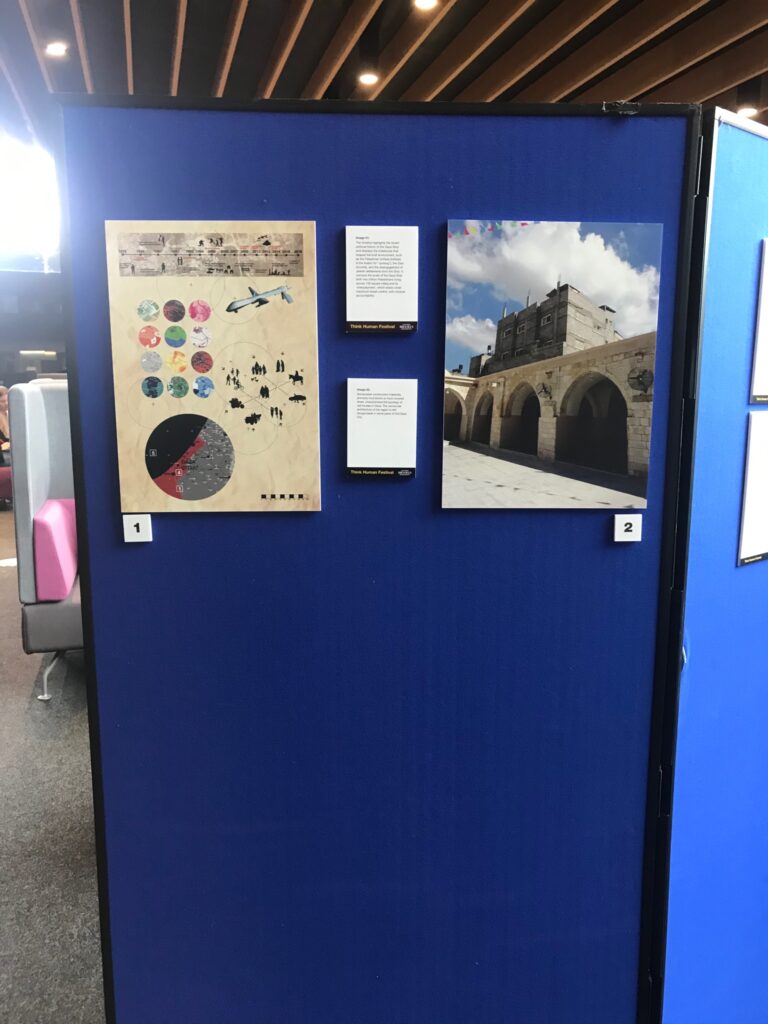

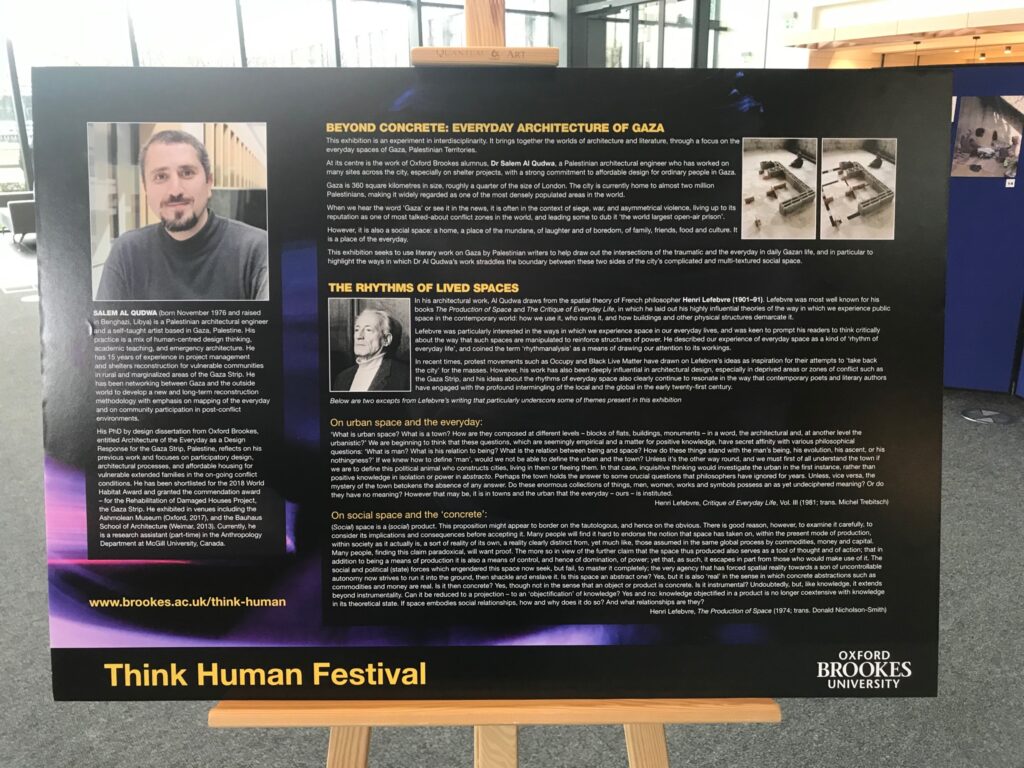

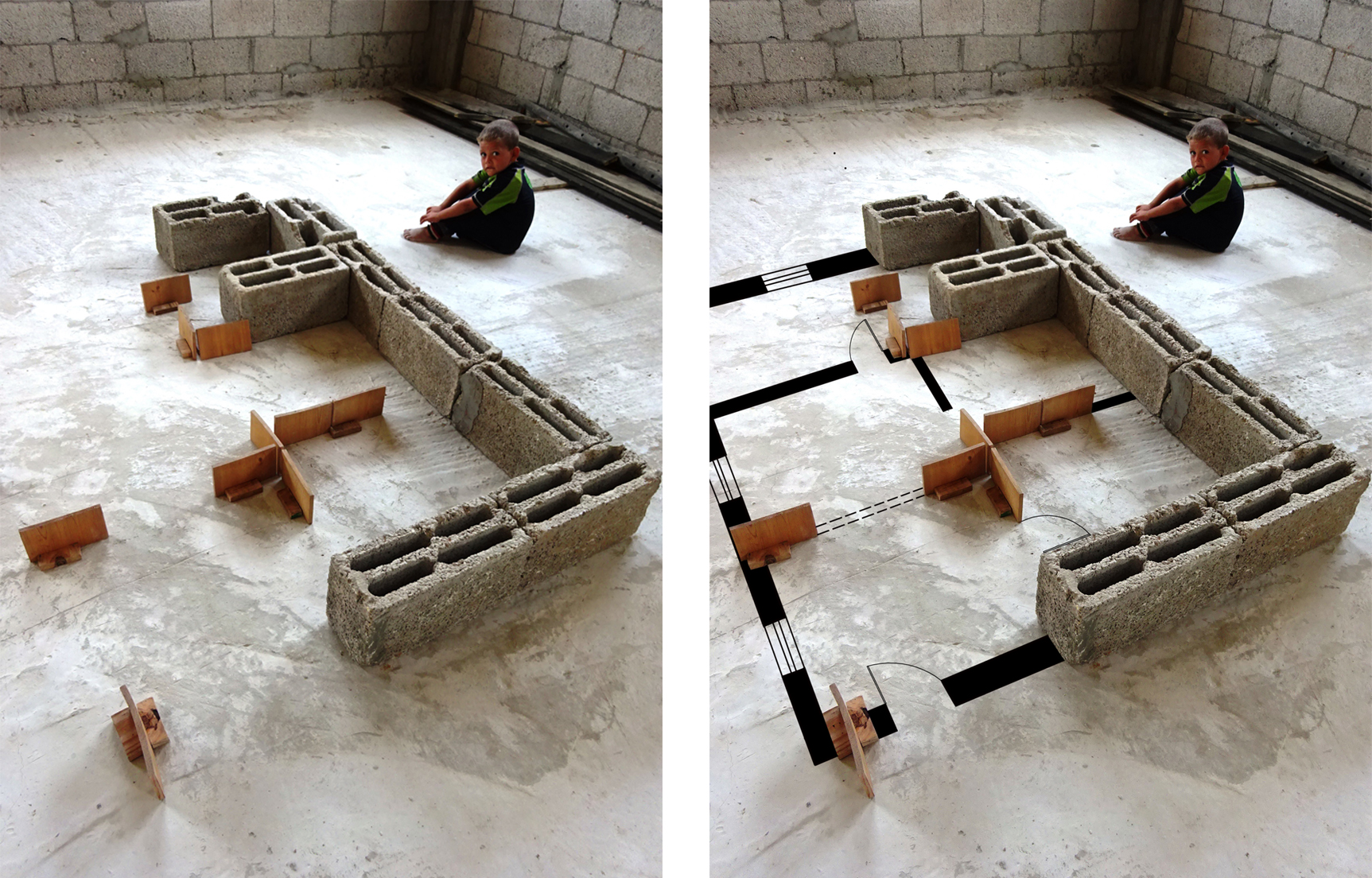

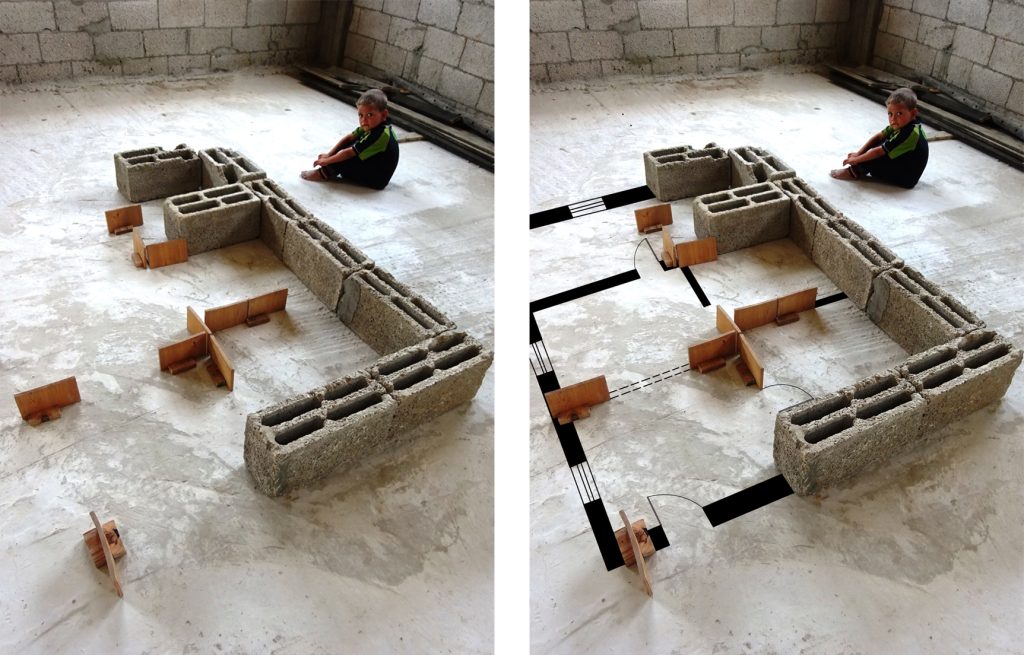

‘Beyond Concrete’ stems from the architectural work of Oxford Brookes alumnus, Dr Salem Al Qudwa, a Palestinian architectural engineer who has worked on many sites across Gaza, especially on shelter projects, with a strong commitment to affordable design for ordinary people in the Strip.

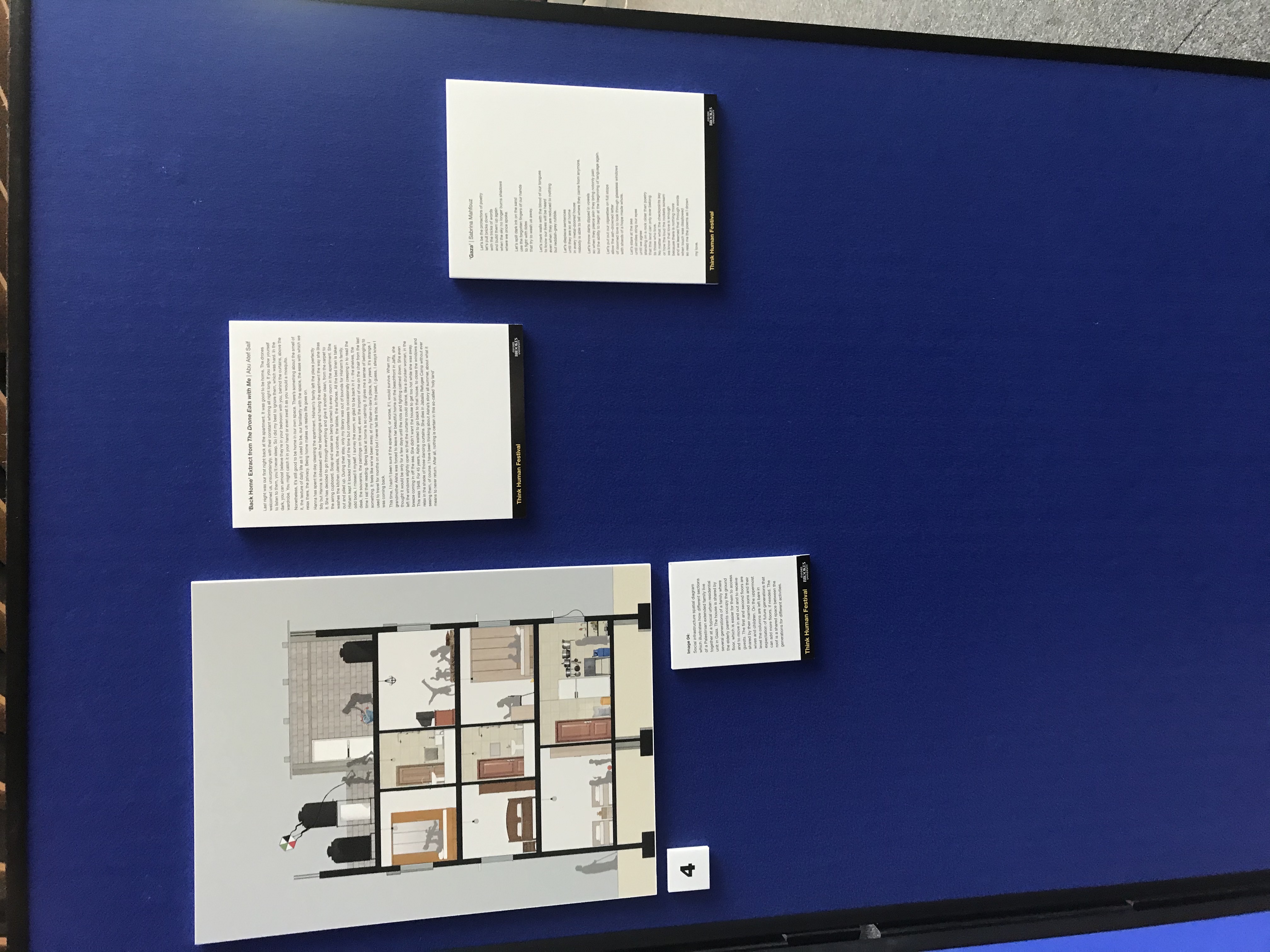

This project seeks to use literary work on Gaza by Palestinian writers to help draw out the intersections of the traumatic and the everyday in daily Gazan life, and in particular to highlight the ways in which Dr Al Qudwa’s work straddles the boundary between these two sides of the city’s complicated and multi-textured social space.

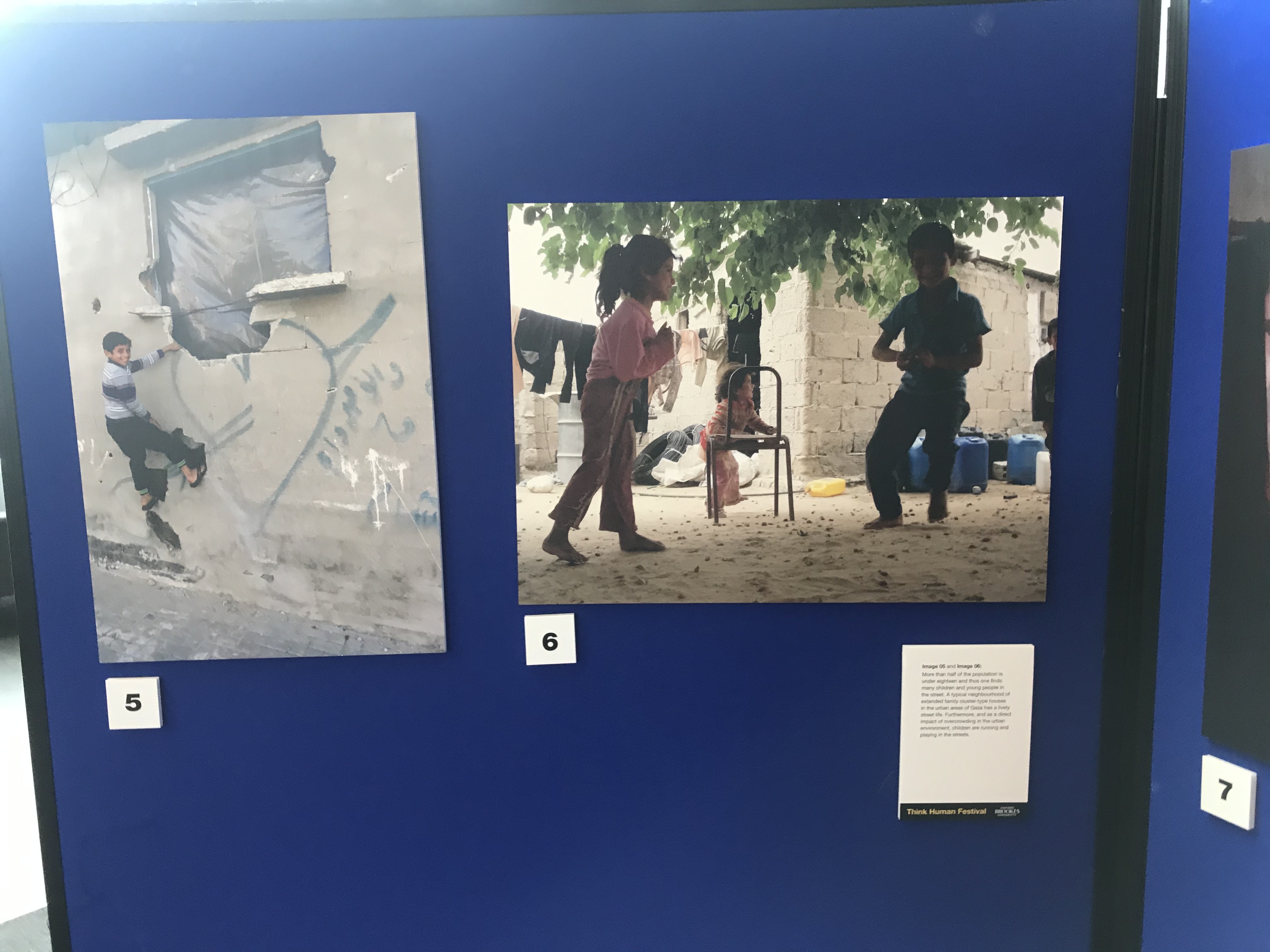

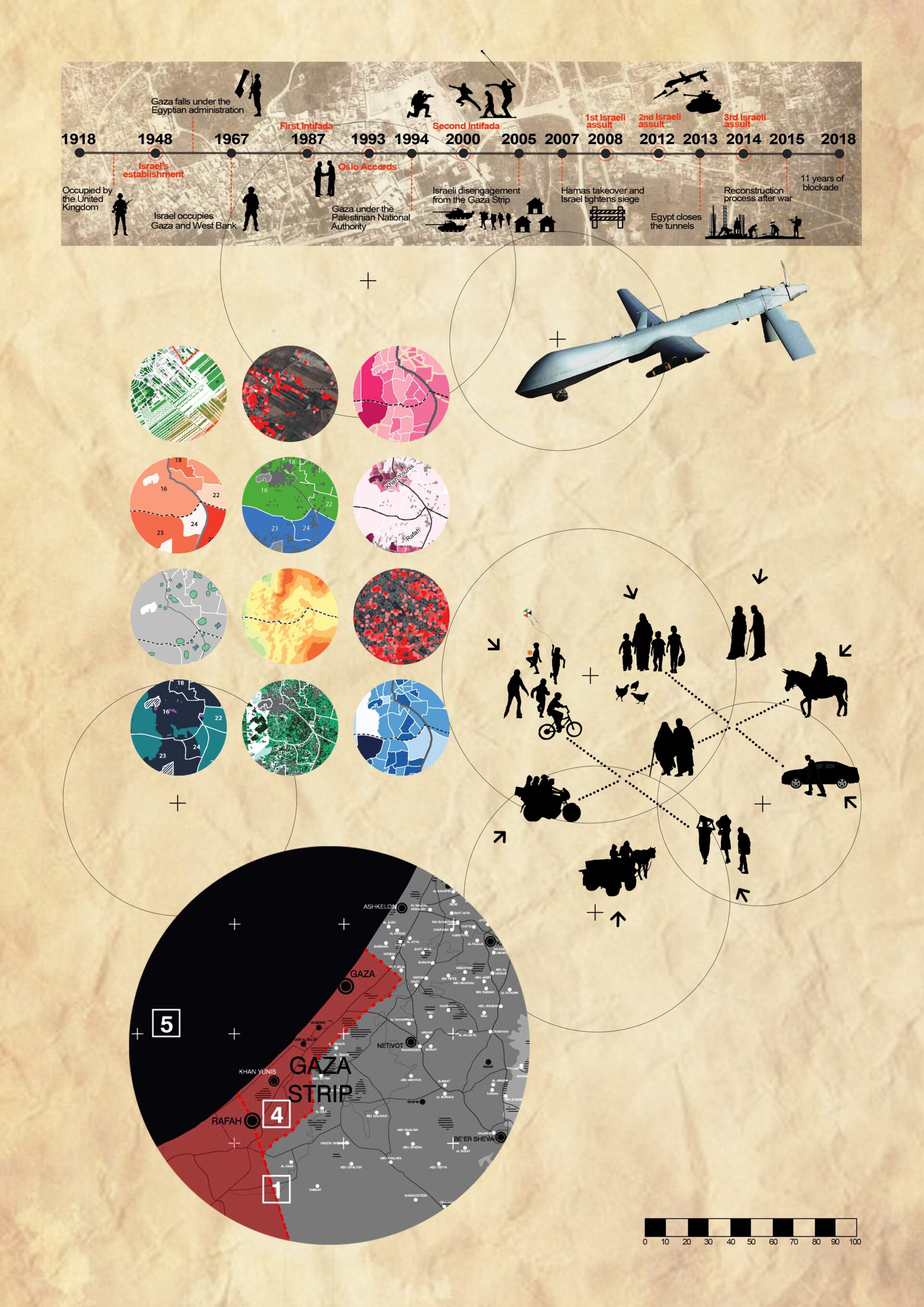

Gaza is 360 square kilometres in size, roughly a quarter of the size of London. The city is currently home to almost two million Palestinians, making it widely regarded as one of the most densely populated areas in the world.

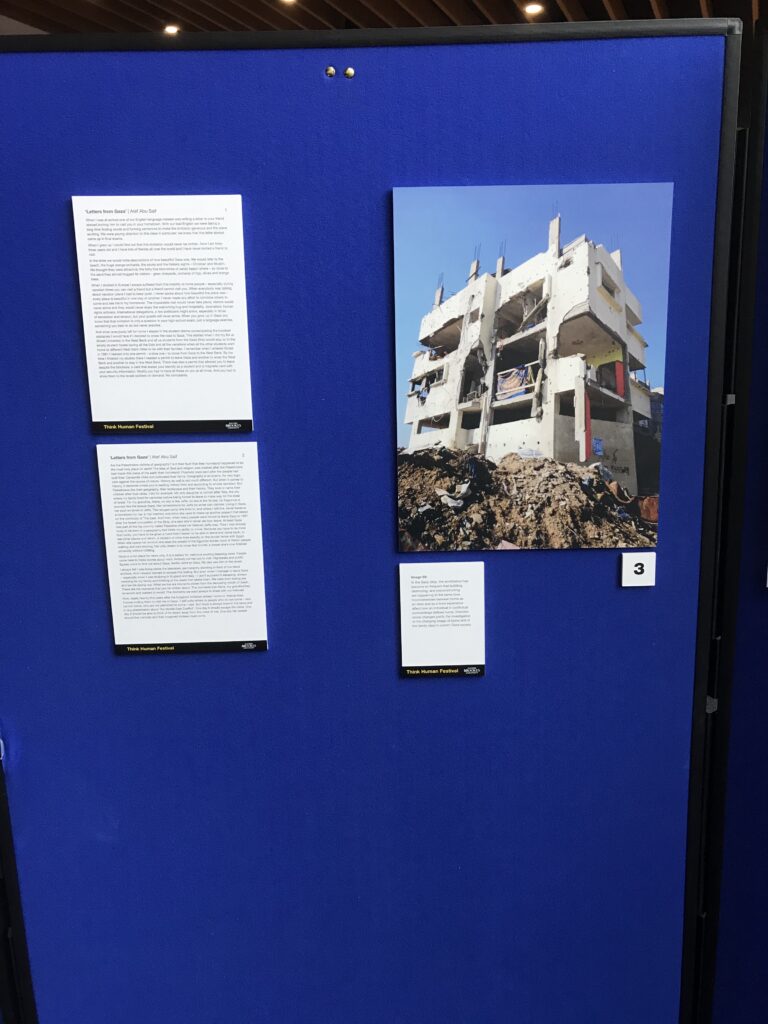

When we hear the word ‘Gaza’ or see it in the news, it is often in the context of siege, war, and asymmetrical violence, living up to its reputation as one of most talked-about conflict zones in the world, and leading some to dub it ‘the world largest open-air prison’.

However, it is also a social space: a home, a place of the mundane, of laughter and of boredom, of family, friends, food and culture. It is a place of the everyday.

The rhythms of lived spaces

In his architectural work, Al Qudwa draws from the spatial theory of French philosopher Henri Lefebvre (1901–91). Lefebvre was most well known for his books The Production of Space and The Critique of Everyday Life, in which he laid out his highly influential theories of the way in which we experience public space in the contemporary world: how we use it, who owns it, and how buildings and other physical structures demarcate it.

Lefebvre was particularly interested in the ways in which we experience space in our everyday lives, and was keen to prompt his readers to think critically about the way that such spaces are manipulated to reinforce structures of power. He described our experience of everyday space as a kind of ‘rhythm of everyday life’, and coined the term ‘rhythmanalysis’ as a means of drawing our attention to its workings.

In recent times, LeFebvre’s ideas have been played out in protest movements such as Occupy and Black Lives Matter, especially in the way these movements have aimed to ‘take back the city’ for its people. However, his work has also been deeply influential in architectural design, especially in deprived areas or zones of conflict such as the Gaza Strip, and his ideas about the rhythms of everyday space also clearly continue to resonate in the way that contemporary poets and literary authors have engaged with the profound intermingling of the local and the global in the early twenty-first century.

Below are two excepts from Lefebvre’s writing that particularly underscore some of themes present in this exhibition

On urban space and the everyday

‘What is urban space? What is a town? How are they composed at different levels – blocks of flats, buildings, monuments – in a word, the architectural and, at another level the urbanistic?’ We are beginning to think that these questions, which are seemingly empirical and a matter for positive knowledge, have secret affinity with various philosophical questions: ‘What is man? What is his relation to being? What is the relation between being and space? How do these things stand with the man’s being, his evolution, his ascent, or his nothingness?’ If we knew how to define ‘man’, would we not be able to define the urban and the town? Unless it’s the other way round, and we must first of all understand the town if we are to define this political animal who constructs cities, living in them or fleeing them. In that case, inquisitive thinking would investigate the urban in the first instance, rather than positive knowledge in isolation or power in abstracto. Perhaps the town holds the answer to some crucial questions that philosophers have ignored for years. Unless, vice versa, the mystery of the town betokens the absence of any answer. Do these enormous collections of things, men, women, works and symbols possess an as yet undeciphered meaning? Or do they have no meaning? However that may be, it is in towns and the urban that the everyday – ours – is instituted.

Henri Lefebvre, Critique of Everyday Life, Vol. III (1981; trans. Michel Trebitsch)

On social space and the ‘concrete’

(Social) space is a (social) product. This proposition might appear to border on the tautologous, and hence on the obvious. There is good reason, however, to examine it carefully, to consider its implications and consequences before accepting it. Many people will find it hard to endorse the notion that space has taken on, within the present mode of production, within society as it actually is, a sort of reality of its own, a reality clearly distinct from, yet much like, those assumed in the same global process by commodities, money and capital. Many people, finding this claim paradoxical, will want proof. The more so in view of the further claim that the space thus produced also serves as a tool of thought and of action; that in addition to being a means of production it is also a means of control, and hence of domination, of power; yet that, as such, it escapes in part from those who would make use of it. The social and political (state) forces which engendered this space now seek, but fail, to master it completely; the very agency that has forced spatial reality towards a son of uncontrollable autonomy now strives to run it into the ground, then shackle and enslave it. Is this space an abstract one? Yes, but it is also ‘real’ in the sense in which concrete abstractions such as commodities and money are real. Is it then concrete? Yes, though not in the sense that an object or product is concrete. Is it instrumental? Undoubtedly, but, like knowledge, it extends beyond instrumentality. Can it be reduced to a projection – to an ‘objectification’ of knowledge? Yes and no: knowledge objectified in a product is no longer coextensive with knowledge in its theoretical state. If space embodies social relationships, how and why does it do so? And what relationships are they?

Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space (1974; trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith)

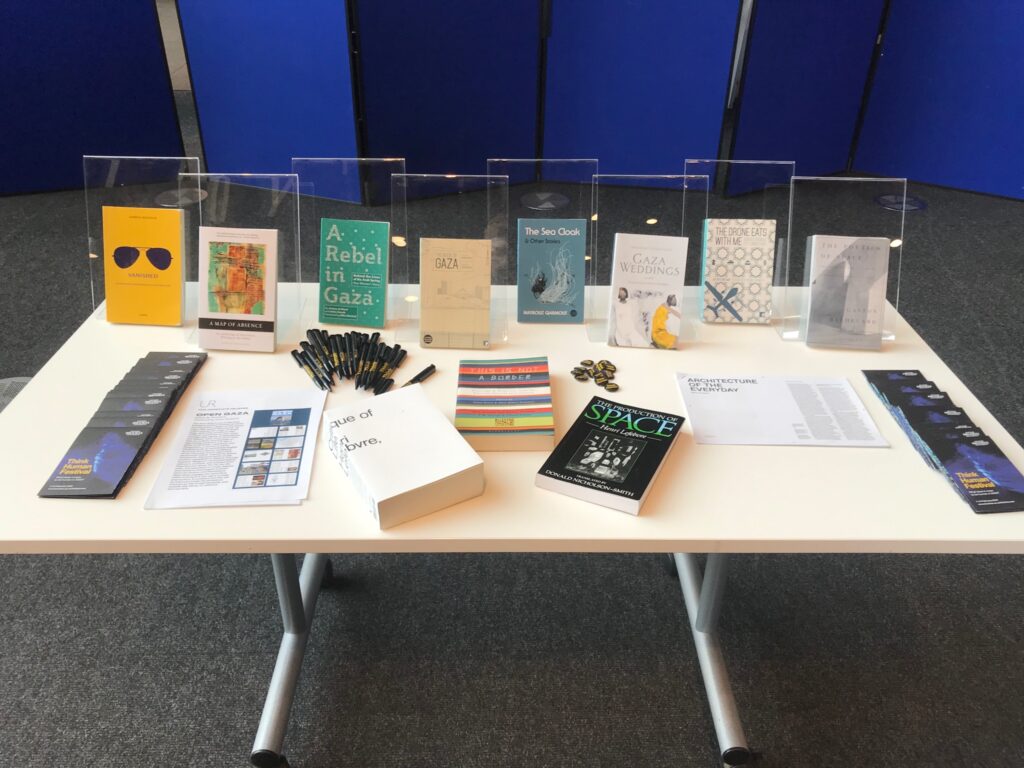

‘Beyond Concrete: Everyday Architecture of Gaza’

Exhibition at Think Human Festival, Oxford Brookes University, 5 February 2020.

The current ‘Beyond Concrete’ project has emerged from an exhibition that Dr Al Qudwa and Dr O’Gorman organised at Oxford Brookes University in 2020, which brought together the worlds of architecture and literature, through a focus on the everyday spaces of Gaza, Palestinian Territories.

The exhibition sought to use literature on Gaza by Palestinian writers to show how Al Qudwa’s work negotiates the city’s social space.