Posted by Daniel O’Gorman

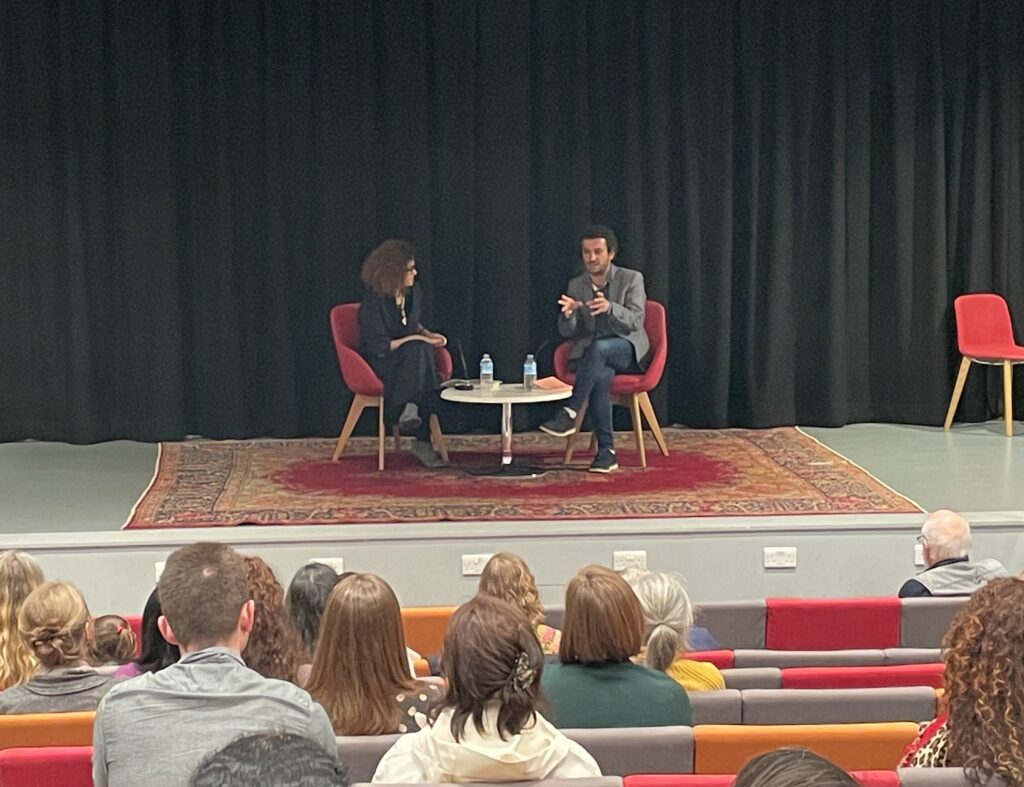

Earlier this week, I attended the launch of Ahmed Masoud’s new novel, Come What May (Victorina, 2022), at SOAS, University of London. The event was chaired wonderfully by fellow novelist, Selma Dabbagh, who asked Masoud a range of searching questions about the novel, as well as about Masoud’s writing process and about his experiences of living everyday life in Gaza (first as part of the refugee community in the Jabalia camp, and later on as a member of the diaspora in London).

Like Masoud’s previous novel, Vanished (Rimal, 2015), Come What May is set in Gaza and revolves around a mystery. In Vanished, the mystery surrounded a missing father; in Come What May, it’s a mysterious death amidst the chaos of the 2014 Israeli bombing campaign against Gaza.

The blurb leads with the following questions:

How does one investigate murder in the middle of a War Zone? Does it matter if a person is killed by an airstrike or a knife?

Having only bought my copy of the novel at the launch event, I can’t say much more about it at present (perhaps a topic for a future blog post), but the intrigue that these questions spark up, as well as the two very engaging passages that Masoud read from it during the launch, make me keen to get started.

As for the event itself: it was heartening to see so many people turn up for the launch on a rainy Wednesday evening. SOAS’ Brunei Gallery in Russell Square was bustling with people who had made the journey to celebrate the publication of the novel.

The conversation began with a discussion of the importance of food in the novel, and the way in which this focus deliberately reflects the centrality of food to everyday social life in Gaza.

It then moved on to the role of literature – both Arabic and Anglophone – in Gazan society. Masoud described writers as ‘part of the fabric of [Gazan] society’. By this he was referring in part to the vital place that prominent Twentieth Century Arabic poets like Mahmoud Darwish, Muin Bseiso (both Palestinian) and Ahmed Matar (Iraqi) continue to hold in the Palestinian collective imagination. In addition, he also emphasised the role of English-language writers in this social fabric: both in Palestinian social life generally and in Gazan social life specifically.

Masoud mentioned that the role of English literature for many Gazans has traditionally had both a pragmatic and an affective value. Its value has been pragmatic because popular English Literature college courses in Gaza have offered opportunities in terms of mastering the English language and of participating in an international literary culture, and therefore of finding work as translators or teachers, or of becoming more able to move abroad.

In addition, Masoud movingly explained that English Literature has had an affective value because of its capacity to offer a kind of imaginative shield against the trauma of living in a state of perpetual warfare. He related a time during the Second Intifada when he found comfort in reading Dickens while bombs fell from the sky outside. Likewise, reading Shakespeare made him ‘feel safe’.

Despite these recollections, Masoud was careful to avoid a romanticisation of English Literature: he jokingly reminded the audience that Robinson Crusoe essentially celebrates a ‘white supremacist’, while also – intriguingly – explaining that his next novel project aims to challenge the coloniality that persists in the English cultural imaginary by rewriting the legend of Robin Hood from a Palestinian perspective.

This rich and engaging conversation covered a variety of other topics, including: the differences between writing in Arabic and writing in English; the challenges of representing women in the novel; the role of surnames in the sometimes uneasy relations between Gaza’s long-established families, on the one hand, and its large refugee communities, on the other; and, finally, what Dabbagh described as the novel’s gripping ‘whodunnit’ mystery style, which, she explained, works to transform a ‘place of political fatigue’ – Gaza – into somewhere readers once again want to explore.

The launch also served to publicise the new PalArt Collective that Masoud has set up in collaboration with a number of other authors, artists, academics and activists, including Dabbagh and another ‘Beyond Concrete’ interviewee, author Nayrouz Qarmout. The Collective commits itself to ‘increasing the number of Palestinian voices and stories in the arts and media’.

Ahmed Masoud’s Come What May is published by Victorina Press.